The Violent Life and Times of Roger Bigod – A Medieval Player of the Game of Thrones?

For almost 250 years, from the time of the Norman Conquest of England in AD 1066, one of the most important families in the Eastern Counties were the Bigods. In later years they would become the Earls of Norfolk and so powerful they could defy the Kings of England, running their territory like the bosses of old-style Mafia crime family.

Despite the fact these were members of a family who lived and died nearly a thousand years ago, in many respects they were a thoroughly modern bunch of ruthless back-stabbers, liars, and rogues who always had an eye on the main prize and didn’t care who they had to trample over or betray to achieve it. In an era of fickle monarchs, when a favorite could fall from power overnight and the following morning might find his head nodding on a pike staring sightlessly into the rising sun, the Bigods were masters of playing this real-life Game of Thrones – and of keeping their heads while those all around were losing theirs!

But where did they spring from?

The first Bigod to make his bloody mark on the pages on English history was Roger Bigod. The month was March. The year, 1067.

Photo of a stone head found at Thetford Priory and believed to be from Roger Bigod’s original tomb. (Public Domain)

Death and Conspiracy

Although Duke William of Normandy – better known as William the Conqueror (although he was also called William the Bastard) – had been crowned King of England on Christmas Day 1066, many parts of England were still resisting Norman rule. This included East Anglia, where one of the leading churchmen – Abbot Aelfwald (or Ethelwold) – had been put in command of the naval and military defense of the East Coast by Harold Godwinson, the last Saxon King of England.

King William I, 'The Conqueror'. (Public Domain)

By the early spring of 1067, King Harold had been dead six months (killed by the arrow that hit him in the eye during the Battle of Hastings) leaving Abbot Aelfwald and his followers holed up in the isolated but seemingly impregnable island fortress of St Benet’s Abbey, in what is now the carefully tended Norfolk Broads, but was then just a maze of rivers, meres, estuaries, mud banks and salt marshes accessible only by boat or across a long, narrow causeway from Horning.

- William of Newburgh: Medieval Vampire Hunter?

- Confessions of a Teenage GhostHunter: Keeping the St Marks Eve Vigil and Looking for the Ghost of Sir Walter Calverley

With all previous frontal assaults on the Abbey having failed, William now put young Roger Bigod in charge of levying the siege of St Benet’s. Until a few years previously, the Bigods (or le Bigots as it was originally spelled) had been a family of poor and relatively obscure knights from Calvados in Normandy (one source describes Roger, born in around 1040, as a “hearth knight” – in other words landless – in the service of Duke William’s half-brother Odo, the Bishop of Bayeux) but the Bigods had earned themselves a reputation as useful people to have around, having earlier alerted Duke William to a conspiracy against him by his cousin and, later, sailing with the invasion fleet to fight at Hastings. Today we’d call Roger a “chancer” (scheming opportunist) who rose to become one of William’s “enforcers.”

An Offer You Can’t Refuse

Recognizing the strength of Abbot Aelfwald’s position, Roger Bigod immediately changed tack and opened negotiations to end the siege without further violence. Aelfwald for his part saw that while the Normans could not get into the Abbey, neither he nor his Saxons could get out so, playing for time, he agreed to a truce and appointed a respected and long serving monk called Essric as his intermediary.

Brother Essric may have served the Abbey loyally for over 20 years but Bigod was a better judge of character than the Abbot and was able to detect that Essric was an unhappy man; A man seething with resentment because he felt he had been overlooked for higher office and was now caught up in a life or death struggle brought on by the Abbot’s dabbling in politics. It was at this point in the negotiations that Bigod made Essric an offer he could not refuse.

If Essric would open the Abbey gates to the Normans in the middle of the night, then not only would Bigod spare the lives of all the monks but he would also make Essric the new abbot “for life” and “raise him higher than any man living within the Abbey... higher than he would ever expect from a friend.”

The deal was struck. Essric agreed to betray the Abbey to his new “friend” during matins (which in a medieval monastic order would have been observed at either 2:00am or 3:00am in the morning) on the 21st of March—which by coincidence also happened to be the feast day of Saint Benedict, the founder of the Benedictine Order followed at St Benet’s.

Payment in Full

So it was that in the dark early morning of the 21st March 1067, the gate was opened, the Normans rushed in, the guards dozing in the gatehouse were overcome, and the Abbey was seized. Then, it was time for Brother Essric to receive his just rewards from Roger Bigod.

First an abbot’s highly decorated cope (in effect a cape) was placed over his shoulders. Then the mitre (ceremonial head-dress) was placed on his head and a crosier (ceremonial staff of office) thrust into his right hand. But, Bigod had one further reward in store for the newly appointed abbot and that was to slip a rope noose over his head.

To Essric’s horror, the other end of the rope had already been hung over the highest point of the gatehouse and, at Bigod’s signal, the Normans began hauling on it, raising Essric “higher than any man living within the Abbey.”

The ruins of St Benet’s Abbey including the gatehouse where the traitorous Essric was hanged and is still said to haunt. (Photo courtesy author)

The Normans may have liked to get their own way and were ruthless in the methods they used to achieve this but they also didn’t like traitors, no matter whose side they betrayed!

Traitor’s Ghost

And that was the short, unhappy career of Abbot Essric, although it is claimed that on the anniversary of his treachery, his screams can still be heard and his ghost seen hanging by a rope from the now ruined abbey gatehouse.

According to some versions of this legend, the date the Abbey was captured and Essric met his untimely end was the 25th of May and that is when the haunting takes place. But, as it is now over 100 years since the last time anyone claimed to see the ghost, (and that witness was so frightened by the experience that he promptly fell into the nearby River Bure and nearly drowned) perhaps the confusion is understandable.

Incidentally, if you are wondering whatever happened to Abbot Aelfwald, in fact he managed to escape out of a concealed postern (side) gate during the confusion immediately following the seizure of the Abbey and eventually made his way to safety in Denmark. After a brief period in exile, he made his peace with the Normans and in due course returned to St Benet’s, where he continued as abbot until his death, peacefully in his bed, in 1089.

Following his activities at St Benet’s, we next encounter Roger Bigod two years later (in 1069) when he and two other Norman warlords, including the then Earl of Norfolk and Suffolk Ralph de Gael (also known as Ralph de Guader) led an army that defeated the Viking king of Denmark Sweyn II Estridsson near Ipswich.

Sweyn and the Jomsvikings at the funeral ale of his father Harald Bluetooth. (Public Domain)

For these services, Roger was generously rewarded by King William but this was nothing compared to five years later when Ralph de Gael fell from power in the failed Revolt of the Earls against William and Roger acquired many of the dispossessed earl’s estates and manors. (The Revolt of the Earls was one of many rebellions, dynastic power struggles, and mini civil wars that plagued England during the mediaeval period.

In the years that followed, in his capacity as the Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk, he acquired so much more property that, by the time the Domesday Book was completed in 1086 (an early survey of England and Wales), King William was the only person to own more land in East Anglia than Roger Bigod.

An engraving of the Domesday Book, 1900. (Public Domain)

Good Luck, Promises and Bribery

The following year (1087) William the Conqueror was on his deathbed but, before he died, he ordered his kingdom be split between his eldest son Robert, who became the Duke of Normandy, and his second eldest son William (better known as William Rufus) who took the throne of England as King William II.

William Rufus, or William II King of England, 1255 (Public Domain)

As Duke Robert and William Rufus were known to loathe each other (along with the usual sibling rivalry, young Rufus was also guilty of playing practical jokes on Robert, frequently involving the contents of chamber-pots) this presented a problem of divided loyalties for those barons who held estates in both Normandy and England, so a plot was hatched to depose King William and unite the two countries under Duke Robert.

Known as The Rebellion of 1088, it lasted less than six months and saw the rebels, including Roger Bigod of Norfolk, defeated and outmaneuvered by William thanks to a winning combination of good luck, promises, and bribery. However, unlike the brutal punishment normally inflicted on defeated rebels, William Rufus took the advice of the barons who had remained loyal to him and opted for leniency.

In the words of one adviser: “If you temper your animosity against these great men and treat them graciously here, or permit them to depart in safety, you may advantageously use their amity and service on many future occasions. He who is your enemy now, may be your useful friend another time.”

William Rufus was actually a far smarter king than history credits him as being. Unfortunately, history is written by the survivors, and Rufus got a very bad press from the Church, who were practically the only people who could read or write in those days. For Roger Bigod, the aftermath of the rebellion was that although he lost some of his lands, he kept his head and went on to regain those estates when he reconciled with the king.

Accident or Murder?

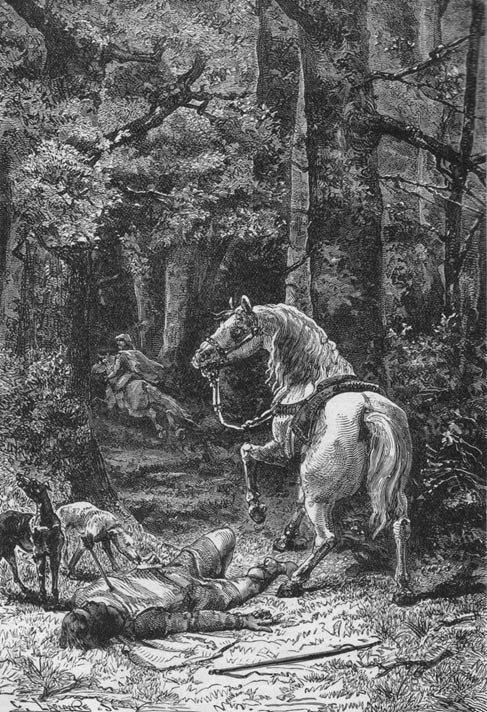

Roger Bigod outlived William Rufus, who was killed in a never adequately explained hunting accident August 1100 in the New Forest, when he was struck by an arrow.

Was William’s death a genuine hunting accident caused by the fatal arrow deflecting off a tree? If so, why did the alleged killer Walter Tirel, who was known to be an excellent archer, immediately flee the country, never to return?

Or, was it an assassination engineered by William’s younger brother Henry who, along with all the other courtiers who were out hunting with the king that day, including Richard de Clare, promptly abandoned the king’s body where it had fallen in the forest and galloped away to nearby Winchester to secure the Royal Treasury and claim the throne as King Henry?

Legend has it that before setting off to go hunting on that fateful day, William said to Tirel “It is only right that the sharpest arrows should be given to the man who knows how to shoot the deadliest shot.” Tirel, incidentally, was married to Richard de Clare’s daughter Adelize.

A rather fanciful depiction of the death of William Rufus from a medieval manuscript. (Public Domain)

Some peasants subsequently recovered the late king’s corpse and carried it to Winchester, where it received a proper Christian burial – though the church chroniclers of the time regarded William’s death as “an Act of God” and a suitable end for “a wicked king”. There again they were not entirely impartial as William and the Church had continually clashed throughout his reign and he had repeatedly appropriated ecclesiastical revenues and tithes for his own personal use.

In fact, in 1096, when the barons complained they did not have enough money to pay the latest tax he had imposed on them, William Rufus – possibly in jest – suggested they should rob the shrines of the saints! For their part, the medieval chroniclers in their monasteries did their best to blacken William’s name, suggesting he was not a committed Christian and still indulged in unnatural, pagan rites.

As recently as the 1980s, English academic and specialist in medieval history Frank Barlow described William Rufus as “a rumbustious, devil-may-care soldier, without natural dignity or social graces, with no cultivated tastes and little show of conventional religious piety or morality – indeed, according to his critics, addicted to every kind of vice, particularly lust and especially sodomy.”

Another depiction of the death of William Rufus of England, 1895. (Public Domain)

Roger Bigod’s Continuing Influence

But back to Roger Bigod who we next hear of being one of the witnesses recorded on the Charter of Liberties which the new monarch King Henry I made as part of his coronation promises. The Charter of Liberties is one of those overlooked events in English medieval history that can now be seen as a forerunner of the more famous Magna Carta. That said, this was no Bill of Rights for the benefit of the Common Man but rather a series of promises and implicit bribes to mollify the kingdom’s earls and barons who were less than enthusiastic about Henry’s accession. Henry may have been the younger brother of the late King William Rufus but many nobles still favored handing the crown to Duke Robert of Normandy.

Whatever the merits of the coronation charter, it is notable that Roger Bigod remained loyal to the new king when a further unsuccessful attempt was made in 1101 to place Duke Robert on the English throne.

There again, Roger may have been influenced by the fact that following his coronation, King Henry granted Bigod a license to rebuild his castles at Thetford in Norfolk and Walton in Suffolk (near Felixstowe) and to build new castles at both Bungay and Framlingham in Suffolk, which were to become the Bigod family’s seats of power for the next two centuries.

The ruins of Bungay Castle, which was the stronghold of the Bigods for 250 years. (Photo courtesy author)

The ruins of Bungay Castle. (Photo courtesy author)

Roger’s Dealings After Death

Roger Bigod died in September 1107 at the age of 67, an impressive age for those times, and his body immediately became the subject of a bizarre (and distinctly ironic given his action 40 years earlier at St Benet’s) dispute between rival clerics.

Because Roger had founded Thetford Priory, the monks there claimed the right to bury Roger’s body (as well as those of his family and successors) as was the custom of the time and as had been set out in the priory’s foundation charter. The monks, incidentally, were not offering to bury Roger out of any particular affection or the kindness of their hearts but to ensure the continued financial patronage of the Bigod family. All those votive candles and chantry masses for their dead souls cost money and would provide a valuable source of income!

However, Herbert de Losinga, the new Bishop of Norwich, argued that the body of the most important magnate in Norfolk should be buried in the new cathedral being built in the most important town in Norfolk, namely Norwich. The bishop also had ulterior motives. He had been the Bishop of Thetford but, six years previously, had transferred the see (the location of the bishopric) from Thetford to Norwich and now wanted to build up the reputation of Norwich as East Anglia’s ecclesiastical hub at the expense of Thetford. And, of course, having Roger buried in the new cathedral would secure the continuing patronage of the Bigod family.

In the event Bishop Losinga (another Norman who was used to getting his own way) had Roger’s decomposing body stolen from Thetford Priory in the middle of the night (in a curious case of history repeating itself, while the monks were distracted celebrating matins) and (according to one source) “dragged” away to Norwich Cathedral for reburial. The current resting place of Roger Bigod’s mortal remains are unknown.

Incidentally, by quirk of ecclesiastical fate, the Abbot of St Benet’s is also the Bishop of Norwich, so St Benet’s Abbey – where the Roger Bigod saga first began – avoided being added to the list of abbeys and priories to be broken up during King Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries. However, as the abbey was redundant by the mid-16th century, the then Bishop of Norwich had it demolished and its building materials ‘recycled’ and sold to help pay off the diocese’s debts. Apart from some fragments of walls, all that now remains is a part of the gatehouse (where Essric came to grief) although these ruins are confusing as 200 years later, during the Georgian era, a large (and now also ruined) windmill was erected in the middle of the gatehouse.

The ruins of St Benet’s Abbey. (Photo courtesy author)

Several hundred yards away from the gatehouse stands a wooden cross (fashioned from oak donated from HM Queen Elizabeth II’s royal estate at Sandringham in 1987) which marks the original site of the abbey’s high altar – and also provides some indication of the scale of the original building.

Wooden cross marks the original site of the abbey’s high altar, with the gatehouse in the far distance. (Photo courtesy author)

Charles Christian is a Norfolk-based writer and journalist. His most recent book is “A travel guide to Yorkshire's Weird Wolds: The Mysterious Wold Newton Triangle” and he can be found at www.UrbanFantasist.com as well as on Twitter at @ChristianUncut

Featured image: Medieval depiction of “royal justice” and the ruthless approach to dealing with dissent (Public Domain)