How to Shrink a Head: The Shuar Creation of Tsantsa

The Spaniards invaded the New World seeking riches. They tortured and maimed, and the religiously inclined Christians did everything they could to stamp out indigenous faiths. They burned shrines and holy places, huacas (sacred places), and mummified ancestral kings, which played an important role in many tribes’ religious practices. The conquistadors (which means conquerors in Spanish) demanded gold, and when some smaller tribes could not supply it or had already turned over what they had, the Spaniards killed or severely injured them. In this way, many of the smaller tribes disappeared, and today we have only a faint understanding of some of their practices, customs, and beliefs. Nevertheless, one indigenous group was able to keep them away. They actually did much more than that; and as such the invaders feared them. The Spaniards called this group the Jívaro, and decided to leave them alone due to their fierce fighting skills and their morbid practice of shrinking heads.

Shrunken Head at Cuenca Museum - Ecuador

A Clash of Cultures

The word Jívaro has no meaning among the indigenous populations for whom it has become a moniker. The Spanish attached this word to a group properly known as the Shuar, the second largest indigenous Amazonian tribe, whose members continue to live the way they always had, unaffected by the outside world. Today they live primarily in southeastern Ecuador between the Marañón and Pastaza rivers (near Cuenca). The term Shuar just means people, and their language is unique compared to other languages in nearby areas. For example, “one, two, three, four, five” is “chikíchik, jímiar, manaint, aínttiuk, uwei.”

When the Spanish invaders used the term Jívaro, it actually referred to four tribes: the Shuar, Ashuar, Aguaruna, and the Huambisa, which had teamed up to drive out the invaders. In 1599, after the Spaniards had demanded gold and maimed some of the tribes’ people to show they were serious, these four tribes joined forces and stormed Spanish settlements, killing more than 25,000 invaders. Knowing the European leaders wanted gold, they gave it to one of them: they held him down and poured molten gold into his mouth. This famous historical episode took place during the Massacre of the Logronos, and some of the ruthless occurrences have gained immortality because of their continued references in movies and television shows, and in both fictional and nonfictional written accounts.

The Shuar did not just kill the raiders; They also took their heads. Later, other Europeans found some of these heads, and they were horrified. Although the faces looked similar to how they had appeared in life, and their features were completely recognizable, the heads were amazingly no larger than the size of a fist.

Shrunken head from the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris (courtesy of Jean-Pierre Dalbéra)

How to Shrink a Head

The Shuar have a long history of shrinking heads. Anytime they went into battle against neighboring tribes, they brought back warriors’ heads, having cut them off at the base of the neck. They carried the heads back to their villages with either headbands or vines, which they slipped through the victims’ mouths, pulled through their necks, and then tied them. They wore the heads like backpacks slung over one shoulder (Flornoy, 1954). As soon as the warriors were able to, they began the shrinking process.

Shrunken Head at Cuenca Museum - Ecuador

Using a large knife, they cut along the back of the skulls until they reached the tops of the heads. Then, they peeled the skin from the skulls themselves. If it stuck near the eyes, nose, or mouth, they coaxed it off with small wooden knives, flint stones, or even shells. Using such instruments, preparers were generally able to free the skin from the skulls without damage. The Shuar tossed the skulls into nearby rivers as an offering to the anaconda, which they believed was the incarnation of a deity. (Some Christians share a similar belief. They think an angel appeared in the form of a snake to bring the first human beings knowledge. They call this fallen angel Lucifer, which means “bringer of light,” hence “bringer of knowledge.”)

With just the intact flesh, the heads were similar to grisly balloons, and the Shuar bound shut the eyes, nostrils, and mouths.

Shuar shrunken head from Stadt Salzburg (Österreich) Haus der Natur (Photo use courtesy of Wolfgang Sauber)

Specific techniques used at that point in the shrinking process varied, but this was the most common: They filled the heads with sand and tied the bottom with a loose knot. Then, warriors placed the heads over an open fire. As the heads heated, the skin shrunk, and sand slowly poured out the bottom, allowing the heads to retain their original shape. Once they had shrunken to the size of a fist, the Shuar tightly tied the necks and artistically enhanced the facial features (von Krenner, 2013). Generally done with wooden instruments and shells, preparers carefully molded the eyes, noses, and mouths to restore their original forms. Finally, they cut the hair proportionately to the heads’ new sizes. The result of this process was a perfectly proportioned human head the size of a fist. They called these heads tsantsa.

Shrunken head compared with normal human skull. (Wellcome Images/CC BY 4.0)

Before getting into the reasons behind this practice and explaining how the heads functioned in subsequent religious and cultural ceremonies, some information regarding technical variations follows: Sometimes, they treated the skin before smoking and heating it over fire. They soaked it in tannins and coagulating substances. Alternately, preparers boiled it in a mixture of water, bark, and plant extracts. When making shrunken heads by means of such variations, they filled the heads with hot sand, which warriors had heated on pottery sherds. This served to shrink the heads from the inside, and as this occurred, the preparers could simultaneously shape and treat the heads’ exteriors with animal fat and other types of oil. Then, the warriors added items to the fire like powdered charcoal and specific types of wood, which darkened the flesh. For this reason, some Caucasian heads might be mistaken at first glance for Native American heads. Rather than the skin’s color, investigators must consider facial features when determining to whom the heads once belonged.

Shuar preserved head from the National Museum of Brazil (courtesy of Dornicke, through Wikimedia Creative Commons)

In a complete description of an alternate method of head shrinking, ethnologist William Jamieson explains that preparers simmered them for approximately two hours, at which point the heads were about two-thirds their original sizes, before they sewed anything. Removing them from the bark and plant-infused water, the preparers turned them inside out, scraped away any undesirable flesh, and then stitched the back of the head. They gathered stones and heated them, and then used them to heat the heads’ interiors and dry them even more thoroughly. The warriors dropped the stones into the neck openings one at a time, taking care that the stones were at the proper temperature and that they did not sit for too long in one location. If this occurred, the stones could scorch the heads, just as leaving a stationary iron on a shirt could ruin it. After the heads dried in this manner, preparers removed the stones and filled the heads with hot sand, which reached into the faces’ small crevices. They shaped the faces’ exteriors using hot rocks again and burned the hair to the correct length. This entire process lasted for weeks, and the warriors worked on them every evening on their way back to their home villages.

A shrunken head from Ecuador. (Wellcome Images, http://wellcomeimages.org/)

Spirits in the Heads

Once they arrived, a celebration ensued in which the heads played a central role. Their significance mirrors a belief found in cultures across the world: a human being is more than just flesh and bones. He or she has a spiritual essence, which has multiple parts.

In early Christianity, believers thought holy individuals’ souls were simultaneously in heaven while also infusing their bodily remains. This complex notion of the souls’ multiple parts came from Egyptian religious beliefs, which held that every person had nine distinct spiritual essences that connected to one another. Likewise, in some forms of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, believers think that one spiritual essence remains with the body while the other travels to heavenly realms at the same time. Tribes in the Americas had similar ideas. People are people, and they all generally think in a similar manner.

The Shuar believe two spirits infuse defeated warriors’ heads. One is akin to a ghost, which could become vengeful and haunt its killer. To placate this personalized spirit, the warrior who shrinks the head wears it around his neck in a celebration designed to take possession of the defeated warrior’s soul. Jamieson explains they had to “paralyze the spirit of the enemy attached to the head so it cannot escape and take revenge upon the murderer.” However, this ceremony was more than just a safety measure to drive away unhappy spirits that might annoy the living. It was also a way to absorb the spiritual power inherent within the human remains.

Shrunken Head at Cuenca Museum - Ecuador

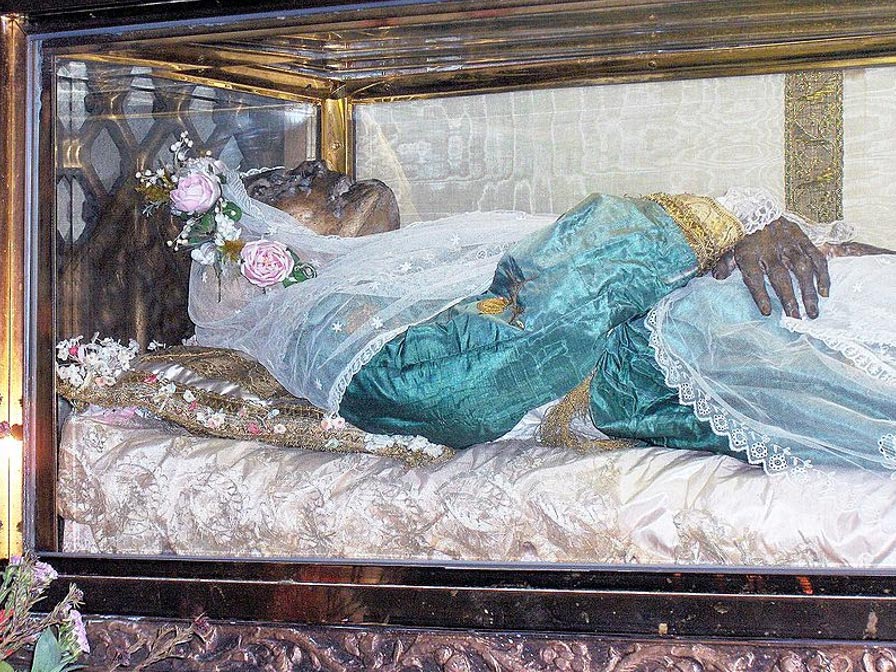

The Shuar call such power tsarutama, and their belief is certainly not unique. In the East, ascetic practitioners believe that the performance of austerities creates a spiritual essence that can benefit others. They believe that this essence, which infuses physical remains, can cause miracles. That is why Shugendo believers sometimes pray in front of mummified bodies, and it is also why the same thing occurs in Christian churches in Europe and other parts of the Americas.

A Catholic mummy, the body of Saint Zita (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Another shrunken head from Ecuador. Exhibited in the Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium. (Public Domain)

Divine Energy

Some think holy people’s bodies have a divine essence that can cure illnesses and provide strength and spiritual direction. The Shuar believe the tsarutama that infuses their adversaries’ heads can likewise be absorbed through a religious ceremony. The tribe trusts that this energy can benefit all of them as a group: that the living can reap benefits from such divine power, as can dead Shuar ancestors. If this does not seem complicated enough, another type of energy also infuses the heads.

A shrunken head. (CC BY 2.0)

In the Shuar language, it is arutam, and it specifically interests the tribe’s warriors. This energy is the accumulation of all the deceased’s martial skills. By absorbing it, the living warrior becomes more powerful. To simplify this, consider the old show and movie Highlander. In the narrative, warriors had a drive to kill others who were like them, and they felt that eventually only one could exist. Therefore, they went around beheading others. Once they had defeated their adversaries, they absorbed their powers. Although this might seem like a strange analogy, it mirrors the Shuar’s beliefs insofar as arutam is concerned.

Shuar warriors covet this energy, so they surmised a means of procuring it: by donning the tsantsa-like necklaces. The warriors make small holes in the heads, run strings through them, and then place them around their necks. In this way, the heads’ presence at festivals provides the entire tribe with tsarutama. Their specific location in contact with warriors’ skin gives arutam to the fighters: more power that can protect themselves and the tribe. In addition, the Shuar had previously given the skulls to the river god, which takes the form of an anaconda. This is believed to provide divine favor, hence divine protection.

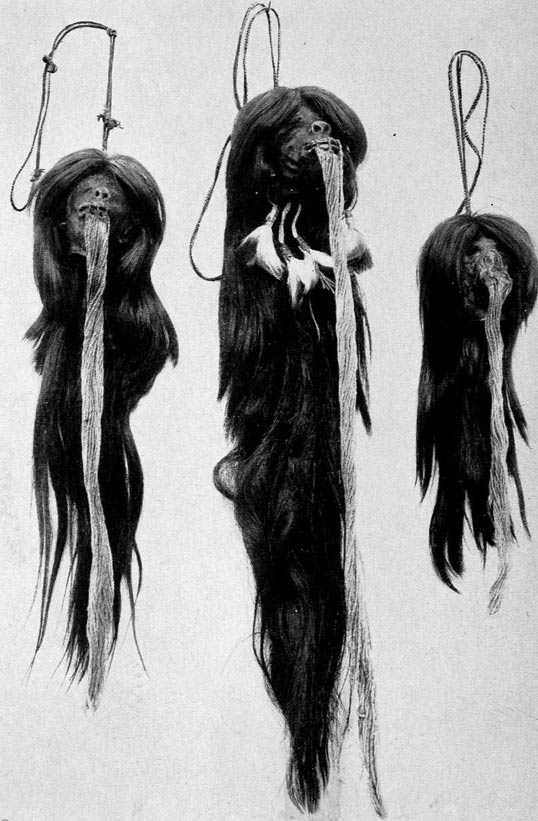

Shrunken human trophy heads from the Jivaro. (Public Domain)

In all, the procurement of enemy heads is an important religious and cultural activity, one that (according to their beliefs) can benefit the tribe and its individual members in many different ways. After the ceremony, the Shuar think that the energy within the tsantsa has been absorbed completely. Their purpose served, the warriors generally discard the heads. It is for this reason that some of them appear in museums and private collections all over the world.

Ken Jeremiah has written more than ten books and dozens of articles. His book Eternal Remains contains more information about the Shuar’s head-shrinking techniques, as well as the reasons behind other forms of mummification in cultures worldwide.

Featured image: Shrunken heads in the permanent collection of "Ye Olde Curiosity Shop", Seattle, Washington state, U.S. (Jmabel/CC BY-SA 3.0)

References

Arriaza, B., Cardenas-Arroyo, F., Kleiss, E., & Verano, J. (1998). South American mummies: Culture and disease. In Cockburn, A., Cockburn, E., & Reyman, T. (eds.) Mummies, Disease and Ancient Cultures. (pp.190-234). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Flornoy, B. (1954). Jivaro: Among the Head-Shrinkers of the Amazon. New York: Library Publishers.

Harner, M. J. (1972). The Jivaro: People of the Sacred Waterfalls. Los Angeles: University of California.

Jamieson, W. (2013). The History of the Shuar. Retrieved from http://www.head-hunter.com/headhunter.html.

Jeremiah, K. C. (2015). Dying to Live Forever: The Reasons behind Self-Mummification. Retrieved from /history/dying-live-forever-reasons-behind-self-mummification-003166.

Jeremiah, K. C. (2014). Eternal Remains: World Mummification an the Beliefs that Make it Necessary. Sarasota, FL: First Edition Design Publishing.

Von Krenner, W. G. (2013). Personal communication.