Castrati: The Superstars of the Church and Opera in 16th Century Europe

“Long live the knife, the blessed knife!” screamed ecstatic female fans at opera houses as the craze for Italian castrati reached its peak in the 18th century. When Farinelli, the most famous castrato of his time, sang in London, one woman squealed "One God, one Farinelli!" Farinelli was later summoned by the Queen of Spain to sing her husband, Philip V, out of his depression, and went on to become the most potent politician in Spain as well as owner of his own opera house.

A castrato was a male singer with a vocal classification of a female or a child’s voice—a soprano, mezzo-soprano, or alto. From about 1550 CE to the late 19th century, those voices were created by castrating boys before they reach puberty, thereby preventing their voices from deepening. A castrato, then, would have the lung capacity and muscular strength of an adult male, and the vocal range of a prepubescent boy. The only difference between a castrato (collectively known as castrati) and a eunuch is that historically most eunuchs were castrated after puberty, thus the castration had no impact on their voices.

Portrait of the castrato singer Domenico Annibaldi (Public Domain)

Castration as a Form of Punishment

Castration as a mean of subjugation, enslavement or other punishment has a very long pedigree. The myth of Attis was one of the earliest examples of the practice of castration as a form of punishment. The myth is of Phrygian origin which became the standard version in Alexandrian and Latin poetry. Attis mutilates himself because he has sexually betrayed his mistress, the mother goddess Cybele. With a flint, Attis strikes off his testicles, the organs which, in his opinion, have led him to sin.

Another, more widespread version of this story represents the angered Cybele herself as the one who avenges her own honor. The essence of both versions is this: Attis yields his virility and survives to enact his new role as a worshipping servant of his overpowering mistress.

Statue of a reclining Attis at the Shrine of Attis. (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Classicist Arthur Darby Nock suggested seeing the practice of castration as a mean of ensuring ritual purity. The eunuch deliberately mutilates himself to achieve, like a young girl or boy, that particular sanctity that will allow him, like Attis, “to serve through his whole life the object of his devotion.” Scholar Walter Burkert added to this by saying that castration puts a man outside archaic society in an absolutely irrevocable way; being neither man nor woman. The eunuch would have no choice but to adhere to his goddess.

Stereotypically, eunuchs served as harem guards in the ancient Near East. They were also valued as court officials and high-level political appointees since they would not be able to start a dynasty which would threaten the ruler. In Constantinople around 400 CE, the empress Aelia Eudoxia was said to have had a eunuch choir-master. By the 9th century, there were eunuch servants and remained so until the sack of Constantinople in 1204.

The Qing Dynasty Cixi Imperial Dowager Empress of China is carried and accompanied by palace eunuchs, before 1908 (Public Domain)

In the early criminal codes of Europe, castration was in use for several of the graver crimes. William the Conqueror brought the method into England to punish rape, and combined it with putting out the eyes which had “looked upon the woman to lust after her.” This method stood as the legal punishment until sixty years after the grant of Magna Carta.

The Beginning of the Castrati

The Apostle Paul's dictum Mulier taceat in ecclesia (women are to be silent in church) is found in I Corinthians 14:34-35: “Let your women keep silence in the churches: for it is not permitted unto them to speak; but they are commanded to be under obedience, as also saith the law. And if they will learn any thing, let them ask their husbands at home: for it is a shame for women to speak in the church.” Another passage in I Timothy 2:11-12 says, “let the woman learn in silence with all subjection. But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man, but to be in silence.”

These passages were interpreted literally, and women were therefore prohibited from speaking and singing in church. Another example of literal interpretations of the bible came from Origen (c. 185 - 254 CE), an early church father from the Alexandrian school, who interpreted the passage of Matthew 19:11-12 literally.

The procedure of castration as punishment during Middle-ages. (Public Domain)

The passage says, “But he said unto them, all men cannot receive this saying, save they to whom it is given. For there are some eunuchs, which were so born from their mother's womb: and there are some eunuchs, which were made eunuchs of men: and there be eunuchs, which have made themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven's sake. He that is able to receive it, let him receive it.”

Origen allegedly castrated himself “for the kingdom of heaven's sake.” Some church fathers, possibly including Pope Clement VIII who was said to be struck by the beauty of the sound of a male soprano voice, interpreted the same passage as providing justification for the use of castrati so that they could contribute their powerful singing ability to church choirs as well as providing a replacement for women, who were not allowed to sing.

Although the church accepted castrati and eunuchs, castration was forbidden under canon law. The church condemned the practice and occasionally excommunicated the person responsible for the surgery, yet simultaneously created a market for castrati by hiring them for its church choirs. By 1789, there were more than 200 castrati in Rome's chapel choirs alone.

The procedure became common in the 1500s. Private patrons, church fathers, or singing companies would approach or be approached by the parents of boys with nice singing voices. Most boys would undergo this procedure at the age of twelve or ‘preferably’ younger, so none of the boys were old enough to give their informed consent.

It was no coincidence that the practice of castration flourished in the poorest areas and among the poorest families. Many families were facing starvation, and the opportunities for castrati were plenty. By 1589, castrati were singing for the Pope in the Sistine Chapel; throughout the 1600s castrati were in high demand for the opera. By the 17th and 18th centuries, four to five thousand boys per year in Italy were castrated. Parents seeking upward mobility and better lives for their children took their little boys to a barber or butcher who would cut off their testicles for a fee. The Santa Maria Nova hospital in Florence even ran a production line, gelding eight boys at once.

The Procedure and the Effects of Castration

Charles d'Ancillon in his Traite des eunuques in 1707 offered a description of one of the standard procedures, which was the severing of the spermatic duct leading to the testicles. Boys were generally drugged with opium (although it was rarely considered worth the risk as it was too dangerous for children). More often, boys were given a hot bath, then had their carotid artery compressed until they were almost comatose, and wouldn’t be conscious to endure the surgery. Another version of the procedure started with a cold bath or a milk bath to numb the area. The actual procedure didn’t involve amputation. Most doctors simply opened up the scrotum and cut the spermatic cords, thereby cutting the testes away from the tissues supporting it. The whole procedure caused the withering and eventual disappearance of the testicles. What happened after the procedure depended on a few things: the age of the child, the competence of the surgeon and the development of the human body. The fatality rate due to the amputation procedure was up to 80 percent.

Medieval medical anatomical illustration. (Public Domain)

Because of the danger and illegality of the operation, surgeons tried to remain anonymous and parents made up stories about how their child fell off a horse or had some hunting accident that required castration. The frequently cited “bite of a wild boar” was among the more unlikely tragedies suffered by little boys in the middle of the eighteenth century. The very image of a wild boar running through an urban conservatory is so heavily metaphorical that the excuse seems like a code word for the operation itself.

A nineteenth century surgeon Benedetto Mojon, in a treatise on the physiological effects of castration published in 1804, explained that a castrato who was neutered at around six years of age would retain, at eighteen, the penis of a six-year-old. But when the operation had been performed closer to the age of puberty, his penis—or what was left of it—would more nearly resemble that of a normal man, with the notable exception that “erection takes place much more frequently than in the case of non-castrated men.”

This piece of information was meant to serve as partial explanation for tales of sexual promiscuity, which Mojon went on to provide: from Juvenal, who criticized the excesses of the Roman eunuchs in his satire, to an account by the forensic doctor Johann Peter Frank in 1779, in which four castrati managed to “know” all the women in a single small town, causing such a scandal that police intervention was required.

However, the same physiological condition that accounted for the castrato’s supposedly enviable position behind closed doors also caused physical deformities that would make the castrated man appear strange. The principal defect was of course the castrato's unnaturally high voice, a result of a larynx that failed to grow to adult size. A castrato’s voice remained that of a voice of a young boy, well trained in singing, which would be backed by an adult chest and lungs, giving the best castrati singers not only high voices but more power to support them. The arms and legs as well as the breasts of the adult male castrato tended to develop to larger-than-normal proportions, making them tall and ungainly. Their features remained more delicate than average males, and as they grew older some of them grew obese.

A caricature of castrato Antonio Bernacchi. (Public Domain)

In 2006, a research group exhumed the remains of Farinelli and examined them. They found, along with the abnormal length of his bones, a build-up of bone along his forehead which indicates a condition called hyperostosis frontalis interna, more commonly found in women than in men, affecting 12 percent of the population, which causes terrible headaches, depression, and other mental problems. This was then connected to historical reports of castrati which emphasized their sensitive nature and erratic mental state. However, this was soon dismissed, as reports of pop and rock stars today often emphasize the same thing without castrations.

When a Castrato Hits the Big Time

Among the survivors of the surgery, the vast majority did not become professional singers because their voice was not of sufficiently high quality. During the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, only one percent of castrated boys developed into successful singers. Even then, as always, different singers had different lots in life. Some sang in church or courts, some in traveling companies, and some retired to teach and compose. Some became low-rent singers doing small performances in small towns, and others spun their singing careers into positions as ministers at royal courts.

The most famous castrato, Farinelli (center). (January 24, 1705 – September 15 or 16, 1782) (Public Domain)

Only a lucky few castrati became rich and famous. These famous castrati had careers like modern rock stars, touring the opera houses of Europe and commanding fabulous fees. They were true divas, famous for tantrums, vanity, extravagant excesses, and sexual prowess. Hysterical female admirers deluged them with love letters, and fainted, clutching wax figurines of their favorite performers.

This may put the castrati in the ‘safe and sexless’ allure of teen idols such as Frankie Avalon in the 1950s or early Justin Beiber in the 21st century, but sexual congress with castrati was not physically impossible.

For Europe’s high society women, the obvious benefit of the castrati’s built-in contraception made them ideal partners for discreet affairs. Soon, popular songs and pamphlets began suggesting that castration actually enhanced a man’s sexual performance, as the lack of sensation ensured extra endurance. When Farinelli visited London in 1734, a poem written by an anonymous female admirer derided local men as “Bragging Boasters” whose enthusiasm “expires too fast, While Farinelli stands it to the last.”

Painting of castrato Farinelli. (Public Domain)

Another castrato, Consolino, made use of his delicate features for his affairs with high society ladies. He would arrive at trysts disguised in a dress before conducting a torrid affair right under the lady’s husband’s nose. A 15-year-old Irish heiress, Dorothy Maunsell eloped with castrato Giusto Tenducci in 1766, although he was then hunted down and thrown into prison by her enraged father. Male opera fans also sought out castrati for their androgynous qualities.

Portrait of Farinelli. (Public Domain)

Even Casanova was tempted. It is said he met a particularly lovely teenage castrato named Bellino in an inn and was bewitched, going so far as to offer a gold doubloon to see the boy’s genitals. In an improbable twist, when Casanova grabbed Bellino in a fit of passion, he discovered a false penis. Bellino was then identified as Teresa Lanti, a woman who had taken up the disguise to circumvent the ban on female singers in Italy. The pair became lovers and he still asked her to dress as a castrato in bed. After their romance ended, Lanti reinvented herself as a female and went on to become a successful singer in more progressive opera houses of Europe where women were allowed on stage.

Portrait of Giacomo Casanova. (Public Domain)

For those men and women who chose, as Dryden put it, to “in soft eunuchs place their bliss/ And shun the scrubbing of a bearded kiss”, these affairs were idealized and safe. But bedhopping could be risky for the castrati. One of the earlier castrati, was assassinated by his lover's furious family and another castrato, who wrote to the Pope requesting permission to marry on the basis that his castration had been ineffective, received the reply: “Let him be castrated better!”

While the Italians called them virtuosi, the French sneered at the castrati as “cripples.” Voltaire's character Procurante sarcastically urged Candide to “swoon with pleasure if you wish or if you can at the trills of a eunuch quavering the majestic part of Caesar and Cato.” In 1753 the scholar Laurisio Tragiense derided “the insolence of the castrati... who will not tolerate any costumes apart from those in which they hope to appear handsome and dashing,” obviously finding the castrati to be anything but handsome and dashing himself.

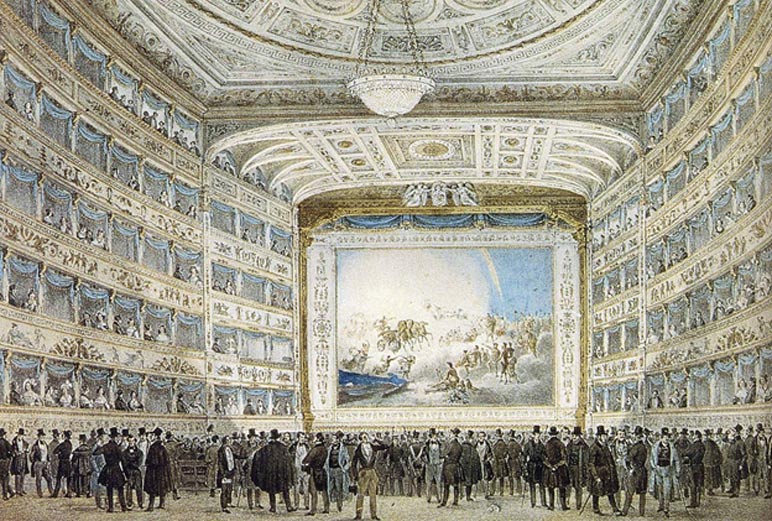

Interior of La Fenice opera house in Venice in 1837. Venice was, along with Florence and Rome, one of the cradles of Italian opera. (Public Domain)

By the 19th century, most people found castration grotesque, leading one virility-obsessed singer with a high voice to splash his posters with the line that he “had the honor to inform the public that he is the father of a family.”

The Last Castrato

The number of castrati declined during the 19th century and in 1870 castrations were banned in the Papal States. In 1878, Pope Leo XIII prohibited the hiring of new castrati by the church. By 1900, there were only 16 castrati singing in the Sistine Chapel and other Catholic choirs in Europe. In 1902, it was ruled that new castrati would not be admitted to the Sistine Chapel, and in 1903 Pope Pius X formally banned adult male sopranos from the Vatican.

Sistine Chapel Choir, 1905. (Public Domain)

Even though the operation was banned in early 19th century, Italian doctors continued to create castrati until 1870 for the Sistine Chapel, and the very last of the castrati, Alessandro Moreschi, went under the knife at the age of seven. Although Moreschi kept performing for the pope until his retirement in 1913, his fame was assured eleven years earlier in 1902, when the American recording pioneer Fred Gaisberg had a few days free in Rome and visited the Vatican Palace, intent of capturing the voice of Pope Leo XIII. As the appointment was cancelled, Gaisberg decided to record the songs of the “Angel of Rome,” as Moreschi was nicknamed.

Alessandro Moreschi, (11 November 1858 - 21 April 1922) (Public Domain)

The voice of the 44-year-old Moreschi was considered past its prime due to his age. He had only one chance to record and made a few nervous mistakes. A second excursion to record him was made in 1904 and the record company made more than a dozen records that preserved the castrato's swansong.

By Alessando Moreschi recorded for G&T by W. Sinkler Darby in 1904. [Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Alessandro Moreschi - 2. Pratesi - Et incarnatus Est Crucifixus (Public Domain Licence)

Featured image: Portrait of Farinelli, circa 1753. (Public Domain)

References

Bergeron, K., “The Castrato as History”, Cambridge Opera Journal, Vol. 8, No. 2 (Jul., 1996), pp. 167-184

Casadio, G., “The Failing Male God: Emasculation, Death and Other Accidents in the Ancient Mediterranean World” Numen, Vol. 50, No. 3 (2003), pp. 231-268

Samantha Ellis, (2002). “Castrati had more fun than you think” TheGuardian.com http://www.theguardian.com/music/2002/aug/05/classicalmusicandopera.artsfeatures

“Castrati Resources on the Web” (2016) MusicOutfitters.com http://www.musicoutfitters.com/castrati.htm

Louden, B., “Iapetus and Japheth: Hesiod's Theogony, Iliad 15.187-93, and Genesis 9-10” Illinois Classical Studies, No. 38 (2013), pp. 1-22

B.A.Robinson, (2007). “Roman Catholic Policies on Castration” ReligiousTolerance.org http://www.religioustolerance.org/rcccast.htm

Elsa Scammell, (2003) “Some Castrati with Interesting Careers” CIX.co.uk http://www.cix.co.uk/~velluti/cast-pics.htm

The Yale Law Journal, “Whipping and Castration as Punishments for Crime”, The Yale Law Journal, Vol. 8, No. 9 (Jun., 1899), pp. 371-386

Esther Inglis-Arkell, (2015). “What did it mean to be a Castrato?” io9.com http://io9.gizmodo.com/what-did-it-mean-to-be-a-castrato-1732742399

Tony Perrottet, (2007). “Why Castrati Made Better Lovers”. TheSmartSet.com http://thesmartset.com/article0806070116/