Atlantis of the Sands and The Lost City of Ubar: Lost, Found, and Lost Again

The myth of the Arabian ‘lost city of the desert’ can be traced to a book of bedtime stories dating from the early ninth century, which was largely responsible for the European romantic perception of Arabia as a place of harems, flying carpets, genies and miscellaneous magic of all kinds – the Arabian Nights.

One Thousand and One Nights

Also known as The One Thousand and One Nights, the story of the book itself is almost as much of a tale of mystery as the stories it includes. The earliest version is thought to have been based on folk tales from India and Persia and was probably written in the ninth century in Syria. Over time it grew, perhaps in an attempt to bulk up the text to reach the number of tales promised in the title, with stories added in the ninth and tenth centuries from Iraq, including many about the Caliph Harun al-Rashid, the fifth Caliph who lived in Baghdad in the late eighth century.

During the reign of the Harun al-Rashid, the city of Baghdad began to flourish as a center of knowledge, culture and trade. 1236-1237 AD. (Public Domain)

In the 13th century more were added from Egypt and Syria.

In 1704 it made its first appearance in Europe when it was translated into French, and at that time even more tales were added including some of the best-known ones such as Aladdin’s Lamp, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, and the Voyages of Sindbad the Sailor. The stories proved so popular that it was translated to English two years later and has been in print ever since.

Clever Scheherazade

The basic premise is well known: A Persian king Shahyrar discovers that his wife has been unfaithful and has her executed. He then marries a succession of virgins, but because of his anger over his first wife’s infidelity he has each one executed in the morning before she has a chance to dishonor him. Eventually he marries Scheherazade, who on the night of their marriage begins to tell him a tale, but does not finish it. In the morning, curious to know how the tale ends, Shahyrar spares her life in order that she can finish the story that night. Scheherazade finishes the tale…but then begins another.

Queen Scheherazade (Public Domain)

Thus starts a series of nightly stories, every one of them ending on a cliffhanger, a sort of medieval forerunner of the weekly TV series. Eventually after a thousand and one nights, the king spares her life and they live happily ever after.

Illustration from "One Thousand and One Nights" (Public Domain)

The Original Lost City

One of the stories is about a man named Abdullah bin Ali Kalibah who goes out into the desert one day to search for his lost camel and finds a magnificent abandoned city decorated with pearls and precious gems, and lofty towers that seem to hang in the air. He gathers up as much treasure as he can carry (fortunately he had found his camel to help him), and later discovers the story of the city.

Where lies the mysterious lost city of Ubar? (CC BY-SA 3.0), (CC BY-SA 3.0) Deriv

It is the City of Many-Columned Iram, built by King Shaddad of the ‘Ad tribe at great expense over many years, but when he came to occupy it he was struck dead by Allah as a warning against pride. A similar story is mentioned in the Quran, where it is said that the city of Iram lies in the region of Ubar and was built by the ‘Ad tribe, but that it was destroyed by a violent sandstorm after its people rejected the message of Islam brought to them by the prophet Hud.

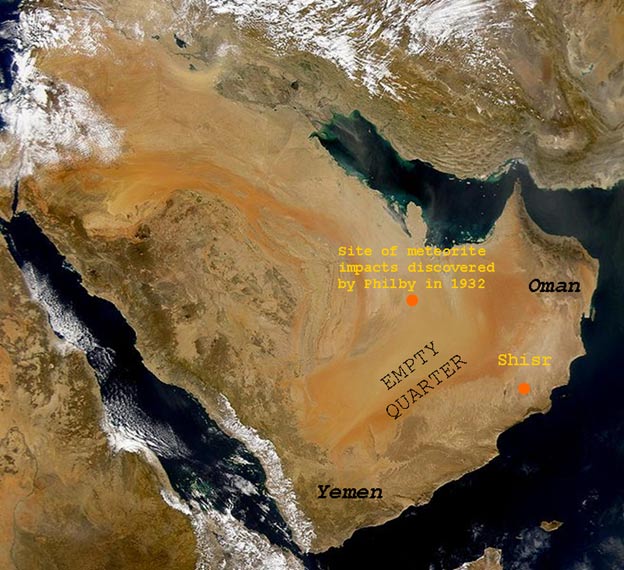

References to Ubar pre-date the Arabian Nights however. The earliest mention is in Ptolemy’s Guide to Geography of 150 AD in which he lists the tribes living in Arabia as including the Iobaritae or ‘people of Ubar’ and locates them in the Empty Quarter. Other historical references in the eighth and 12th centuries place it ‘between Shisr and Sanaa’ or ‘between Hadramawt and Subub’, and in the 11th century the Arab historian Nashwan bin Said al-Himyari describes Ubar as ‘the land which belonged to the ‘Ad in the eastern part of the Yemen; today it is untrodden desert owing to the drying up of its water’.

All of these are broadly in the southern part of the Empty Quarter and in southwestern Oman, inland from the area where frankincense was produced, a highly-valued incense which was grown along this coast and traded with the countries to the north via camel trains across the Empty Quarter.

Rub' al Khali or Empty Quarter is the largest sand desert on earth. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Early Attempts to Locate Ubar

Although Ubar was known from the Quran it was an encounter by Bertram Thomas, the English explorer who in 1931 became the first westerner to cross the Empty Quarter, that sparked modern interest in it as being a place that might actually exist and could be found.

In his book Arabia Felix, Thomas describes his coming across well-worn ancient camel tracks on the plain at the southern edge of the Empty Quarter at approximately 18°45'N 52°30'E, and his Arab guides explaining that they were ‘the road to Ubar…it was a great city, our fathers have told us, that existed of old; a city rich in treasure, with date gardens and a fort of red silver [gold?]. It now lies buried beneath the sands in the Ramlat Shu’ayt [a southern region of the Empty Quarter], some few days to the north’.

Tantalizingly, one of his guides recalled being there as a boy whilst grazing his father’s herds (although that seems a funny thing to be doing in the desert), and could describe with clarity what he had seen.

“He had come upon a complete earthenware pot, with broken pot-sherds of red and yellow, a part of grindstone, two coffee pestles of black polished stone, and two large white rounded blocks of stone, notched at the edge and both alike, but each so big as to require two men to lift it... But these humble things he had never associated with a mighty city, though it had surprised him to find pottery in the sands, for no true nomad of the desert carries earthenware pots on his camels.” But with no time to spare in his attempt to cross the great sand desert Thomas did not have the opportunity to follow the tracks.

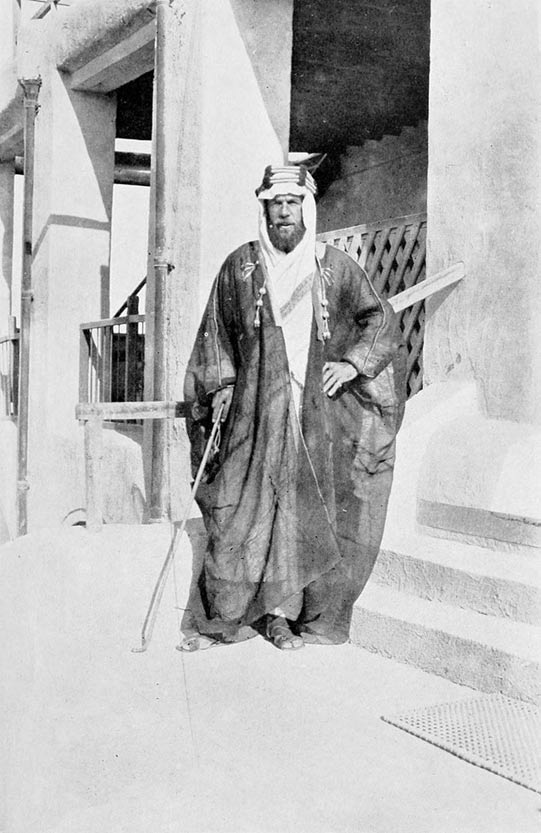

The following year Thomas’s great rival, Harry St John Philby, upset by having failed to be first across the Empty Quarter, hoped to score a coup by finding Ubar instead. According to his Bedouin companions the ruins of Ubar had occasionally been found and lost again deep in the shifting dunes south of Riyadh, so Philby aimed to cross the desert through this area.

St John Philby (1885-1960) in Riyadh (Public Domain)

Semi-human Monsters

After searching for weeks in the stifling heat one of his guides returned excitedly with a lump of blue-black glassy rock and the claim that he had found two castles half buried in the sand. Philby elatedly anticipated them as being the remains of Ubar, “the city of the wicked king destroyed by fire from heaven and thenceforward inhabited only by semi-human mono-membranous monsters.”

As they hurried towards the site Philby recorded that their first sighting of Ubar was a “thin low line of ruins riding upon a wave of the yellow sands”. Sadly, his excitement was short-lived; when they got there what he actually found were two craters surrounded by blackened slag and lava. From a distance and at ground level their jagged edges resembled crumbling ramparts, but up close it was obvious that they were natural formations of some kind, and Philby quickly concluded that what they had found was an ancient volcano. As he recorded in his diary “I knew not whether to laugh or cry…”

A Find Out of this World

He never knew it, but what he had actually found was neither a volcano nor the home of ‘semi-human mono-membranous monsters’ but something more dramatic – the twin impact craters of a large iron-nickel meteorite, now estimated to have been around 3,500 tons in mass and five to ten meters (16.5 to 33 feet) in diameter, hitting the earth’s atmosphere at a speed of about ten miles (16 km) per second, splitting into pieces and exploding with the force of a nuclear bomb on impact in the desert, instantly liquefying the surrounding sand and turning it to glass.

A satellite photograph of southern Arabia showing suspected sites of a lost city, and the meteorite impact zone. (Public Domain)

In all likelihood the incident had even been witnessed; around one hundred years earlier a spectacular fireball had been observed blazing over Riyadh and exploding with a flash over the horizon. A few years after Philby’s death an expedition by the National Geographic magazine and the Saudi Aramco oil company revisited the Wabar Craters as they are known and excavated a very large iron meteorite, one meter (3.2 feet) across and weighing over two tons, the remnant of the original projectile.

Wabar Meteorite cross section (Public Domain)

So Ubar remained unfound. When Thomas later recounted his tale of the mysterious ‘road to Ubar’ to T.E. Lawrence (‘Lawrence of Arabia’), Lawrence started to enthusiastically refer to it as the ‘Atlantis of the Sands’, and told friends that he was convinced that the remains of an Arab civilization were to be found in the desert and that he wanted to put together an expedition to search for it. Due to his untimely death in a motorcycle accident shortly afterwards he never did, and the next glimpse of the enigma was not until the 1950’s when a geologist named Wendell Phillips re-discovered Thomas’s camel tracks (describing them as “a highway of deeply cut parallel camel tracks over a hundred yards wide”) and was able to follow them for about twenty miles (32 km) until he lost them beneath the dunes.

Lost City Found…

There matters rested again until the late 1980’s when a film-maker and amateur archaeologist named Nicholas Clapp persuaded NASA to use the imaging radar on board the new Space Shuttle to look at the Empty Quarter in search of the elusive camel tracks, arguing that places where the tracks converged might indicate ancient watering holes or cities. The radar images successfully revealed a wealth of ancient trackways, some of which indeed converged at a site in the southern Empty Quarter – at a place called Shisr, which had long been known as an abandoned well with some nearby ruins, but which was not thought to be of any great age.

Shisr showing the sinkhole which dominates the site, and ruined walls above it. (CC BY 2.5)

In 1992 NASA duly announced with much fanfare that ‘the lost city of Ubar has been found’, a triumph of modern remote sensing technology and American space expertise over a mystery that had stumped historians and explorers for literally centuries.

A ground expedition was put together by the explorer Ranulph Fiennes and the remains of a walled enclosure about two hundred feet across were found, including the foundations of eight towers; these were a key feature because ‘pillars’ or towers are specifically mentioned in the description of Iram in the Quran as being a prominent feature of the city. A second notable feature was that much of Shisr had collapsed into a sinkhole, potentially another link with the stories of Ubar from the Arabian Nights which mentions the city as having being destroyed so totally ‘as if it had never existed’.

Satellite image of Shisr today, with modern houses to left. The restored walls of the Shisr fort with can be seen with towers at the corners, together with the collapsed sinkhole in its center (dark areas are shadows). (Google Earth)

…and Lost Again

Excavations started that same year led by Dr Juris Zarins, but it was not long before doubts surfaced whether Shisr really was Ubar. No one disputes that there was a small fortress at Shisr dating back to the third millennium BC, or that it lay on the lucrative frankincense trail, but nothing concrete has ever been found that links it to Ubar or the Ubarites. Perhaps most importantly, the small size of the fort really rules it out of being a city that matches the Arabian Nights description – it appears to simply be a waystation or caravanserai.

Every indication is that it was simply a staging post on the frankincense trail for the caravans prior to their entry to the sands of the Empty Quarter, a place where camel trains were assembled and men and animals watered before heading into the desert proper. Shisr was simply never big enough to have been a ‘city’ by any stretch of the imagination, and the few small turrets at the corners of its fortified wall does not make it a ‘city of towers’ either.

Even Zarins, initially very enthusiastic about the site being Ubar, has distanced himself from such claims in later interviews, pointing out that the historical evidence usually refers to Ubar as a region and a people, not as a town or city. He blames the Arabian Nights for romanticizing Ubar and creating a city that never was.

So Where Might it Be?

The lack of a clear description in the Quran of where Iram of the pillars alias Ubar might be has allowed plenty of speculation on its location. Dr. Abdullah al Masri, Assistant Under-Secretary of Archaeological Affairs in Saudi Arabia has suggested it might be Obar, an oasis in eastern Saudi Arabia.

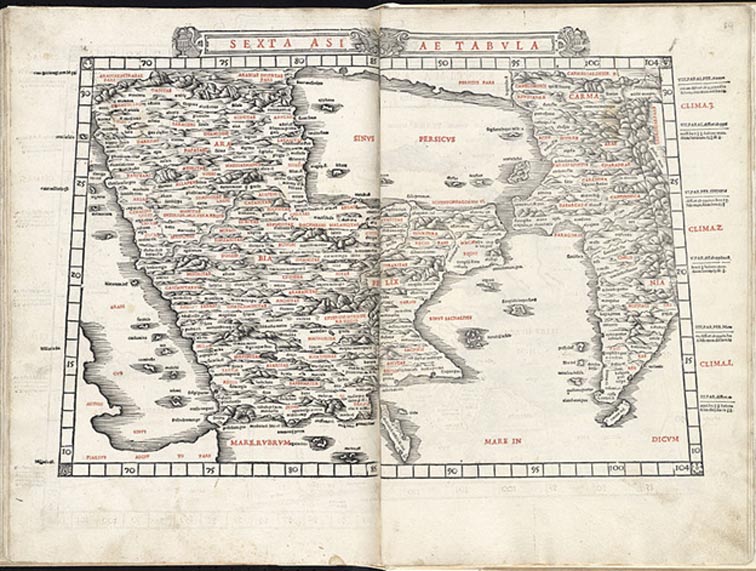

Map of Arabia published by Pencio, Jacopo Date: 1511, based on Ptolemy’s map of 150 AD (CC BY 2.0)

Ranulph Fiennes, who led the original ground expedition and who was very familiar with Oman due to his years in the country when in the British Army, thinks it could be ‘Omanum Emporium’, another town indicated on Ptolemy’s map, which has also never been found but whose name ‘emporium’ suggests it could be an Omani market town such as Nizwa or Izki, about 400 miles (643 km) northeast of Shisr.

Radar imagery uncovered a city buried under sand in Oman. This is the radar image of the region around the site of the lost city of Ubar in southern Oman, on the Arabian Peninsula. The ancient city was discovered in 1992 with the aid of remote sensing data. Archaeologists believe Ubar existed from about 2800 BC to about 300 BCE. (Public Domain)

Others have suggested Iram is in Iran, Yemen, or Egypt. Right now the field is wide open and the honest truth is we simply don’t know. Worse still, even if we find a previously unknown desert city, unless it has distinctive towers or artifacts with references to the Iobaritae, it won’t be easy to show conclusively that it is Ubar. Arabia’s most famous lost city is still lost.

David Millar is a science writer and author of ‘Beyond Dubai: Seeking Lost Cities in the Emirates’.

Featured image: An artistic expression of a city from the One Thousand and One Nights. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

References

The Road to Ubar: Finding the Atlantis of the Sands, Nicholas Clapp, Houghton Mifflin, 1999

Atlantis of the Sands: The Search for the Lost City of Ubar, Ranulph Fiennes, Bloomsbury, 1992

Beyond Dubai: Seeking Lost Cities in the Emirates, David Millar, Melting Tundra Publishing, 2014